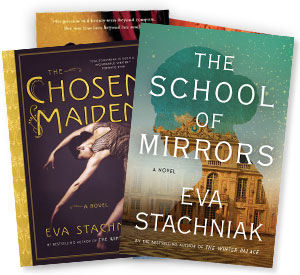

My latest guest blog post from Writing Historical Novels:

In Poland where I grew up, Catherine the Great has always been an object of hatred and scorn. After all, she is the Tsarina who, with the help of Prussia and Austria, wiped Poland off the map of Europe for over a hundred years. She is the empress who crushed the last Polish uprising and made Poland’s king – her one time lover – her prisoner. The Poles still cannot forgive her the bloody massacre in the suburbs of Warsaw during the Polish uprising of 1795. She is routinely referred to as “this horrible woman” and a “hypocrite”. Since mid-eighteenth century she has been a symbol of imperial Russia, a woman feared and despised, hated and cursed. A view shared by generations of Turks and descendants of Ukrainian Cossacks.

In Canada, where I’ve lived for the last thirty years, I have met another Catherine. Her Western biographers – and she has had many of them – stress that she was one of the most formidable women rulers in modern history. She is referred to as an enlightened empress, a legislator who did not shy from the first comprehensive attempt to reform Russia’s laws, a masterful politician with steady nerves and clear goals to strengthen Russia. She is hailed as a builder of magnificent palaces, gardens, schools, hospitals, and orphanages. She is seen as a collector of art, which can still be admired in St. Petersburg, and a passionate woman who didn’t hide her desires, taking younger and younger lovers as she aged.

It was this contradiction that provided the initial inspiration for turning to Catherine as the subject of my novel. Then, the more I learned about Catherine the Great, the more she intrigued me. How did she manage to transform herself from a minor Prussian princess who arrived in Moscow at 14 without a word of Russian at her disposal into the powerful autocrat of All the Russias? How did she survive the long and hard years in a loveless marriage, deprived of her children who were considered too important to be raised by their mother? How did she win over the hostile court for whom she was a mere “Housefrau with a pointed chin?” How did she manage to push aside her immature husband and reach for the throne of Russia?

In my subsequent research I have found many answers to these questions. Each biographer of Catherine the Great – and she has had many excellent ones from J.T. Alexander to Robert Massey – stresses some other aspect of her character. She was smart, charismatic, pragmatic and hard working. She had clear goals and stuck to them. She knew which course of action was politically feasible and which should not be attempted without patient building of support – like the abolition of serfdom which she wished to implement but gave up in the end. She was also clear that Russia’s prosperity was her ultimate goal and that she was not going to detour from it.

From a Polish perspective, none of this may matter much. Russia’s gain has been Poland’s loss and another look at Catherine the Great won’t change it. To me, the very act of re-examining who Catherine was has been a fruitful journey.

Polish Language Site